The following Toronto real estate article is quite interesting and will have a major effect not only to Tenants in Ontario. But also to toronto commercial real estate investors looking to buy multi-residential Properties and current owners.

Last week, the Province of Ontario brought an abrupt end to universal rent control. The move reversed a policy enacted by the outgoing Wynne government just last year, which expanded rent control to all tenants in Ontario, and ensured that any yearly rent increases would be capped at the rate of inflation. For some tenants, that’s no longer true, as any leases signed in new units completed after November 15th are not protected. Why is that the case?

Will ending rent control create greater housing supply and push prices down? Photo by Marcus Mitanis.

For the Ford government, the elimination of rent control is part and parcel of an “Open for Business” ethos that strips bare the social safety net in favour of a more free market. Ending rent control follows the basic logic of any deregulation. Since rent control limits long-term revenue potential for landlords and property managers, it also ostensibly restricts the market’s ability to deliver greater supply. If rents can’t rise to meet demand, it means that developers won’t be as incentivized to build, and demand pressures on existing housing stock will only continue to drive prices up.

There’s a simple and coherent logic to these arguments. Assuming rent control makes new development significantly less viable, it’s reasonable to conclude that rents would only become more expensive for those trying to enter the market. Like any high-demand commodity, housing requires responsive supply in order to prevent rapid price escalation. If prices aren’t allowed to go up, then they also won’t come down.

The Ford government’s decision to eliminate rent control has already drawn praise from much of the real estate industry, including the Greater Toronto Apartment Association, the Real Property Association of Canada, and the Federation of Rental-housing Providers of Ontario. Benjamin Tal, deputy chief economist at CIBC, shares the same view, going so far as to argue that the “only way” to push developers to provide more supply is to allow them to charge higher rents.

Writing in (yes) the Toronto Sun, Ontario Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing Steve Clark argues that ending rent control “will encourage both big developers and small landlords to create more affordable apartments. This will help control and lower housing prices while providing consumers with more housing options.”

Conversely, Clark frames the Wynne-era rent control expansion as a system “that divides a city into ‘haves’ and ‘have nots.’ For those who are lucky enough to already have an apartment, rent control helps control costs. However for those who have not yet been able to find a rental, rent control freezes thousands of families out of the housing market altogether because nobody can afford to build the new apartments the city needs.”

***

Before delving into the relationship between rent control and housing supply, it’s important to understand what rent control accomplishes, and why it exists. Facing an existing housing shortage, the Wynne government expanded rent control to all units in 2017, capping year-over-year rent increases, and hopefully preventing existing tenants from becoming priced out of their homes.

Imagine, for instance, a tenant renting a one-bedroom apartment in a recently completed condo building for $1,500 per month in 2017. If the unit is not rent controlled, the landlord is free to raise the yearly rate to whatever the free market will bear. If an apartment renting for $1,500 could draw $2,000 on the market, the landlord is free to raise rents to meet market demand. For the tenant, however, that could mean facing a rent they can no longer afford to pay. It could mean having to move out.

Assuming the unit is rent controlled, however, any yearly increase on the $1,500 rent would be capped at the rate of inflation, which was pegged at 1.5% in 2017, and 1.8% in 2018 and 2019. A 1.5% increase on $1,500 amounts to $22.50. For the tenant, being able to stay in their home is obviously good. If we recognize housing as a fundamental right, a policy that ensures consistent affordability for tenants accomplishes a clear and worthwhile goal.

Downtown Toronto’s contemporary housing stock is mix of 20th century rentals and 21st century condos. Photo by Marcus Mitanis

Downtown Toronto’s contemporary housing stock is mix of 20th century rentals and 21st century condos. Photo by Marcus Mitanis

But is this expansion of tenant security an inherent constraint on supply — one that subsequently creates an inequitable system of rent-protected ‘haves’ and priced out ‘have nots’? Assuming that rent controls have some impact on supply, are the harms of removing tenant security a necessary and justifiable outcome? The debate about rent control hinges on these two central questions:

1) Does universal rent control inherently prevent adequate housing supply from coming to the market?

2) Is pricing tenants out of their homes an acceptable social outcome — whether or not it spurs long-term supply gains?

To help us understand the relationship between rent control and supply, Ontario’s history of rent regulation policies is a useful starting point. Ontario’s first rent control legislation was introduced in 1975. As the University of Toronto’s J. David Hulchanski explains in a 1997 paper, the combination of dramatically low vacancy rates (which hovered at 1% by 1974), a lack of new rental construction, and the ‘stagflation’ era’s quickly rising consumer price index, put tenants at risk before the introduction of rent controls.

In the 70s, rent control legislation came about as a response to a pre-existing supply shortage. In the decades that followed, however, new purpose-built rentals almost disappeared from Ontario’s urban landscape. In 1992, Bob Rae’s NDP temporarily exempted new construction from rent control regulations for the first five years. Then, in 1997, Mike Harris’ government decided to overturn universal rent control permanently, retroactively exempting any units completed after 1991. The so-called ‘1991 loophole’ allowed for landlords of newer units to raise rents past the rate of inflation. How did all of this impact purpose-built rental supply?

As Hulchanski points out, the introduction of rent control in the 1970s came about as a response to an existing shortage of rental supply. Published this year, a report from the Federation of Metro Tenants Associations’ (FMTA) by Phillip Mendonça-Vieira offers broader context. Mendonça-Vieira argues that the legalization of condominiums in 1967 and the reform of income tax laws in 1972 disincentivized the development of new rental units before rent control was ever introduced.

Once developers were allowed to build multi-unit condominiums, the construction and financing of purpose-built rentals became much less attractive. With a condominium, a developer is able to make a profit as soon as units are sold, making for much easier project financing. Today, pre-construction sales and bank financing mean that the viability of a development is largely secured before a shovel hits the ground. By contrast, developing a rental-project is a comparatively long-term bet; the revenue is generated over decades, not days. (Indeed, many of today’s purpose-built rental developers are companies with long-term interests, such as pension funds and REITs).

In parallel to the influx of condominiums – which increasingly constitute Toronto’s de facto rental supply — Mendonça-Vieira identifies taxation changes, beginning in 1972 and continuing through the 80s, as a key factor curtailing new rental construction:

For the first time, the government began to tax capital gains – with the notable exception of the sale of a primary residence. The government changed the tax treatment of losses due to capital cost allowances, the rate at which capital costs can be depreciated, and removed the ability to pool rental buildings and defer the recapture of depreciation upon the sale of a property. It also prevented investors from outside the real estate business from claiming capital cost deductions or offsetting income via rental losses, and it altered how and which “soft” construction costs like architect fees, building permits, etc, can be deducted, amongst other changes.

In practical terms, this meant that purpose-built rental buildings became a far less attractive investment class, while homeownership became far more attractive. Taxing all capital gains except primary residences, in addition to the variety of demand and supply side incentives and subsidies being offered at the time, is a considerable enticement for diverting money into homeownership. With regard to rentals, being able to depreciate a building tax-wise at a faster rate than its actual economic depreciation can have a large impact on after-tax returns. Rental buildings become more profitable over time, as inflation and debt repayment lowers ongoing operating costs; prior to these reforms, high-earning professionals could use losses generated by rental properties to offset their higher marginal tax rates, and they could use liberal capital cost allowance rates to defer income tax until they sold their property.

In addition, Mendonça-Vieira points to a variety of secondary factors — like the introduction of the Goods and Service Tax in 1991 — which meaningfully, but mostly unintentionally, impacted the viability of new rental development.

But what happened after Mike Harris’ government lifted rent control on new units? Speaking to the Toronto Star’s Tess Kalinowski, FMTA executive director Geordie Dent argues that “there is no empirical evidence that rent control affects rental housing development one way or another. When rent control was gutted by Harris in 1997, we were promised thousands and thousands of new units. They did not materialize.” There’s an important caveat to this.

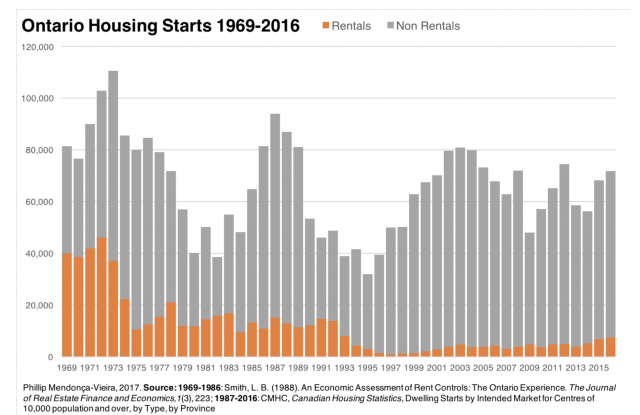

Image via FMTA / Phillip Mendonça-Vieira

Image via FMTA / Phillip Mendonça-Vieira

When rent control for new development was first lifted, Ontario was mired in the worst of the real estate crash of 1989-1996. The market did not fully recover until the early 2000s, when Toronto’s current condominium boom began to re-shape the fabric of the city. Nonetheless, a comparison of rent control laws and rental development hardly shows a straightforward causality. Rent control didn’t ‘kill’ purpose-built rental development in the 70s any more than it revived it in the 90s. But what did it do in 2017?

According to a recent report by Urbanation, rental development has actually accelerated since the Wynne government’s expanded rent control legislation came into effect. “A total of 2,635 purpose-built rental apartments started construction during Q2-2018, raising the total under construction count to 11,073 units — 69% higher than a year ago in Q2-2017 (6,539). The inventory of rentals underway is now higher than the total number of units built since 2005 (10,871),” the report shows. In fact, the current rental construction rate is the highest seen in three decades.

So far, empirical evidence shows that rent control has not crippled the purpose-built rental market. Yet, it seems naive to assume that the revenue limits imposed by rent control won’t have any impact of new purpose-built development. The supply-side arguments made by Tal, Clark, and various voices in the real estate industry all have a solid rational basis. Rent control does limit the long-term revenue potential for developers, which likely has some impact on their ability or willingness to deliver new supply. In a city facing a record-low rental vacancy and record-high rents, more housing is necessary. All things being equal, rent control probably makes it harder to deliver supply — but the same is also true for most types of market regulation.

As Toronto faces a shortage of housing supply, it’s easy to identify regulations as a culprit — and rent control is perhaps the easiest target to single out. While it’s probably true that rent control may limit the viability of some new development, the same charge could be levelled at anything, from the updated Toronto Green Standard (which pushes higher upfront costs of green building), to tower separation distances (which keep high-rise buildings 25 metres apart), and even labour regulations in the construction industry. But we choose to implement these regulations anyway — and rightly so.

Regulations are not inherently good or bad, but some are necessary to prevent market forces from trumping more fundamental human rights and social priorities. The City of Toronto demands green building because it accomplishes environmental goals, and it institutes tower separation guidelines because they protect livability for tenants. Similarly, strict labour rules keep workers safe, even if it means Toronto construction moves slower than Beijing’s. Considering that rent control is merely one of many determinants of housing supply, the security of tenure afforded to tenants trumps the benefits of market liberalization.

On the other hand, there are some regulations that we could do without. For example, Toronto’s restrictive single-family zoning (coined the ‘yellowbelt’ by planner Gil Meslin) prevents new housing supply from being introduced to most of the city, arguably pushing environmentally destructive sprawl to the suburbs. Then there’s Toronto’s mandatory parking minimums, which require that most new developments include parking — even though downtown buyers do not demand it. (In addition, there are numerous potential Pigovian subsidies and market incentives that the government can levy to encourage purpose-built rental housing, including the development charges rebate program recently scrapped by the Ontario government).

It’s fair to critique regulations (be they provincial or municipal), but the clear benefits — and limited inherent harms — of rent control make it a poor target.

But what about the system of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ that Minister Clark warns us about? Does rent control create a privileged few? Only if we assume that the people who rent are otherwise disproportionately privileged. They aren’t. In fact, Hulchanski argues that rent control can prevent discriminatory landlords from raising prices on ‘undesirable’ tenants — who have historically included women, queer and trans people, and visible minorities — while Mendonça-Vieira points out that rent control can help long-term residents remain in their homes as their neighbourhood gentrifies, preventing displacement.

Ultimately, rent control protects the rights that everyone ought to have. And even if the removal of these protections was crucial to increased supply, we must ask ourselves a simple question: is removing a tenant because of their inability to pay the market’s highest rent an acceptable outcome for our society to condone?

Even in the most optimistic scenarios, the elimination of universal rent control will not bring a massive and immediate influx of units to the market. In the short- to medium-term, people will lose their homes. Make no mistake, the reality that most of our future housing stock has already been built means overwhelming majority of Ontarian renters will remain protected under rent control — even decades from now. But not all of us. The new system allows residents to be pushed out of their homes. Whether that happens to 50 or 5,000 people, it isn’t right.

***